Monday, 2 November 2009

Wednesday, 30 September 2009

Sunday, 20 September 2009

Thoughts after preaching from the book of James

The Epistle of James says, when Christian communities are bolstered with self-regard, when they bask in the approval of the rich and powerful and convince themselves that the correct belief alone will justify them, they deceive themselves. This is especially the case when they simultaneously deny justice and dignity to those on the margins, to labourers, to people living on the edge – those who present to us the tangible judgement of God on the way we arrange our lives and our world.

In his 1977 book Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger, which prefigured much of the more recent concern among evangelical churches for people and planet, Ron Sider tells the story of a US pastor who causes great offence in the pews by delivering a fearsome manifesto denouncing the wiles of the rich and the mistreatment of poor people and workers. His congregation in turn accuse him of sedition and of ‘pulpit politics’. But he points out to them that, in fact, every word he has used is sourced directly from the likes of Isaiah, from Amos and from James. They call themselves biblical people, but the Word is apparently unknown to them when it comes to acting justly, seeking mercy and walking humbly before God as a social reality.

Yet the uncomfortable fact is that more often than not the Gospel reverses our ‘normal’ judgments, our idea of what is ‘natural’ and ‘right’. If we are to judge correctly, and not find ourselves hoist with our own legalistic petard, we need to discover what it is to live and to have faith with integrity, says the Epistle of James. This means seeking the knowledge of God that comes to us through merciful action, not through pious sounding words or recourse to the protection of religious tradition. In these terms, the Christian message is un-common sense – something rare and precious – rather than mere ‘conventional wisdom’.

In his 1977 book Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger, which prefigured much of the more recent concern among evangelical churches for people and planet, Ron Sider tells the story of a US pastor who causes great offence in the pews by delivering a fearsome manifesto denouncing the wiles of the rich and the mistreatment of poor people and workers. His congregation in turn accuse him of sedition and of ‘pulpit politics’. But he points out to them that, in fact, every word he has used is sourced directly from the likes of Isaiah, from Amos and from James. They call themselves biblical people, but the Word is apparently unknown to them when it comes to acting justly, seeking mercy and walking humbly before God as a social reality.

Yet the uncomfortable fact is that more often than not the Gospel reverses our ‘normal’ judgments, our idea of what is ‘natural’ and ‘right’. If we are to judge correctly, and not find ourselves hoist with our own legalistic petard, we need to discover what it is to live and to have faith with integrity, says the Epistle of James. This means seeking the knowledge of God that comes to us through merciful action, not through pious sounding words or recourse to the protection of religious tradition. In these terms, the Christian message is un-common sense – something rare and precious – rather than mere ‘conventional wisdom’.

Wednesday, 16 September 2009

Chanting the slogans of Empire, and making alliance with Caesar

Despite protests to the contrary, modern Christianity has become willy-nilly the religion of the state and the economic status quo. Because it has been so exclusively dedicated to incanting anemic souls into Heaven, it has been made the tool of much earthly villainy. It has, for the most part, stood silently by while a predatory economy has ravaged the world, destroyed its natural beauty and health, divided and plundered its human communities and households. It has flown the flag and chanted slogans of empire. It has assumed with the economists that "economic forces" automatically work for good and has assumed with the industrialists and militarists that technology determines history. It has assumed with almost everybody that "progress" is good... It has admired Caesar and comforted him in his depredations and faults. But in its de facto alliance with Caesar, Christianity connives directly in the murder of Creation.

(from "Christianity and the Survival of Creation" pp 114-115 Wendell Berry)

(from "Christianity and the Survival of Creation" pp 114-115 Wendell Berry)

Monday, 17 August 2009

Climate Change debate in the Australian Parliament

I've read what I have been able. I've worked really hard to understand. And this is the conclusion I've come to both for the Government and the Opposition.

Armed with cost-benefit analyses, they report that saving the planet for its inhabitants may be all very well and good… but it is simply too expensive for the capitalist economy to afford. So, bad luck any real climate change.

Armed with cost-benefit analyses, they report that saving the planet for its inhabitants may be all very well and good… but it is simply too expensive for the capitalist economy to afford. So, bad luck any real climate change.

Monday, 27 July 2009

Really Taking a Break

More interesting reading from overseas clergy friends

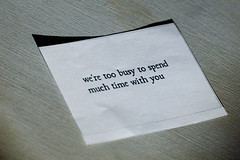

Work has always created pressure on us as people, but the tools we have recently developed – ostensibly to make our lives easier, like all tools are meant to do – have created untold tensions within people. Always-on email, instant responses and decisions required, the need for each moment to turn a profit. When we feel a sense of control over it, this can make work rewarding and exciting; when we lack that control it creates anxiety.

A recent article in The Observer entitled ‘Welcome to the Age of Exhaustion‘ William Leith described his own battles with crunching fatigue and illness that was no more than a symptom of modern living.

What we need of course is a holiday. A ‘holy day’. An extended Sabbath. A time in the tradition of Jubilee when we are liberated from our labour. In modern terms: a time to down tools.

We may mock Orthodox Jews for their often comic attempts to get round the Sabbath obligation to do no work. But, as is so often the case, beneath the comic veneer is a sound principle that we are foolish to have abandoned: we need regular times away from our tools.

Too often, because of the business of our lives (or the shocking lack of annual leave afforded US citizens) we try to pack so much into our holidays. We spend fortunes visiting far off places and trying to consume new experiences, all the while clicking away on cameras and nipping into internet cafés to catch up. We drive and fly back jetlagged and exhausted… only to have to return to 50 weeks work.

In his article Leith quotes a New York doctor, Frank Lipman, who has identified this condition of being at the end of our tether with a succinct diagnosis. These people, he says, are ’spent.’ He is spot on. In a world of ubiquitous consumer ideologies, what better way to describe those who cannot compete any more? They are spent people, with no more in the bank.

I believe part of the art of being on holiday has to be a deliberate attempt to down tools, to step away from our technologies and simply be present. Having been ‘created from the earth’ an essential part of our re-creation should be to reconnect with that founding substance of the earth.

The explorer and prolific walker Sebastian Snow once described what happened on a long walk:

“By some transcendental process, I seemed to take on the characteristics of a Shire [horse], my head lowered, resolute, I just plunked one foot in front of t’other, mentally munching nothingness.”

This is recreation in process: mentally munching nothingness. The art of the holiday, the art of downing tools and entering a period of Sabbath, is no more than a decision to strip away the wires that tie us, to walk, and sit, with no pressure to spend.

Enjoy your time away, whether that’s a holiday in your own living room, or to some farther shore. I hope it feels like the river when it flows, joyful, surprising and unfolding.

Work has always created pressure on us as people, but the tools we have recently developed – ostensibly to make our lives easier, like all tools are meant to do – have created untold tensions within people. Always-on email, instant responses and decisions required, the need for each moment to turn a profit. When we feel a sense of control over it, this can make work rewarding and exciting; when we lack that control it creates anxiety.

A recent article in The Observer entitled ‘Welcome to the Age of Exhaustion‘ William Leith described his own battles with crunching fatigue and illness that was no more than a symptom of modern living.

What we need of course is a holiday. A ‘holy day’. An extended Sabbath. A time in the tradition of Jubilee when we are liberated from our labour. In modern terms: a time to down tools.

We may mock Orthodox Jews for their often comic attempts to get round the Sabbath obligation to do no work. But, as is so often the case, beneath the comic veneer is a sound principle that we are foolish to have abandoned: we need regular times away from our tools.

Too often, because of the business of our lives (or the shocking lack of annual leave afforded US citizens) we try to pack so much into our holidays. We spend fortunes visiting far off places and trying to consume new experiences, all the while clicking away on cameras and nipping into internet cafés to catch up. We drive and fly back jetlagged and exhausted… only to have to return to 50 weeks work.

In his article Leith quotes a New York doctor, Frank Lipman, who has identified this condition of being at the end of our tether with a succinct diagnosis. These people, he says, are ’spent.’ He is spot on. In a world of ubiquitous consumer ideologies, what better way to describe those who cannot compete any more? They are spent people, with no more in the bank.

I believe part of the art of being on holiday has to be a deliberate attempt to down tools, to step away from our technologies and simply be present. Having been ‘created from the earth’ an essential part of our re-creation should be to reconnect with that founding substance of the earth.

The explorer and prolific walker Sebastian Snow once described what happened on a long walk:

“By some transcendental process, I seemed to take on the characteristics of a Shire [horse], my head lowered, resolute, I just plunked one foot in front of t’other, mentally munching nothingness.”

This is recreation in process: mentally munching nothingness. The art of the holiday, the art of downing tools and entering a period of Sabbath, is no more than a decision to strip away the wires that tie us, to walk, and sit, with no pressure to spend.

Enjoy your time away, whether that’s a holiday in your own living room, or to some farther shore. I hope it feels like the river when it flows, joyful, surprising and unfolding.

Talking to myself after yesterday’s worship service

A friend of mine in the USA sent me the following article early this morning. After my experience of worship yesterday it seemed to be very much addressed to me. So I've done a bit of re-writing on it to make it mine too.

The idea of a Misery Index has been around for a long time — since the early ’70s. It’s actually an economic bellwether that’s determined by factoring inflation and unemployment. Economists reason that when unemployment and inflation are high, that generally spells misery for consumers.

The current Misery Index (for June 2009) is 8.16.

Yesterday was a particularly “low” day in our worship service. It was cold. Many people were away with all manner of ailments, many related to winter. Others had been on holiday and were ill. Others just stayed home, I’m told, because they just don’t feel like coming out at the moment. We struggled with hymns, Bible reading and Prayers. Many parents with children were absent, so our Sunday School was “light on”. I preached as fervently as I could, but the faces looking back at me seemed blank and bored. I came home to a time of “low prayer” – O Lord help me, I feel as if I have been laid low. (Sort of like a ‘Lamentation’.

How does one preach when people are miserable – and the preacher feels miserable too!. Along with the above “winter stuff” I have people in my congregation who have lost their jobs, maybe they might lose their homes, their retirement packages. They’ve watched their stock portfolios plunge in value, and many are delaying retirement because they simply can’t afford to retire right now. People are struggling to make ends meet. How does one preach in such contexts?

This brings me to the Mystery Index, which is suggested to me by what I remember of Gabriel Marcel’s ruminations on the general subject. How one can keep faith and have hope when utterly miserable has got to be the greatest mystery of all time.

Marcel, a philosopher and playwright, has been dead for more than 25 years now, but he’s still worth a read. Called by some a Christian existentialist, he addresses our subject in his book The Mystery of Being, originally delivered as the Gifford Lectures at Harvard.

Although Marcel doesn’t refer to a Mystery Index, in my thinking the Mystery Index is determined by the factors of faith (what Marcel calls “creative fidelity”) and hope. His ideas about being and having, availability and nonavailability are worth review. He says that too often people talk about trying to “have” this or that, when in fact, it isn’t a question of having something, such as love or hope, but being love and hope. A key component in this mystery is how we relate to others. When we make ourselves available to others, we link ourselves with their world and experience. We are present to them and for them, in communication with them. We are at their disposal when they’re in need. They aren’t alone.

When we are present to others, i.e., available to others, they are enabled, or empowered, to be faith and to be hope in miserable times. The problem with faith is that it must be constant and must have someone or something as its object. While God is the ultimate object of faith, our preaching helps mediate that object.

As for hope, Marcel argues that a person who is hope doesn’t accept the current situation as final. Hope isn’t fixed on any particular method of deliverance. Surgery to remove a cancer, for example, may not produce a desired result. But as a person of hope whose hope isn’t linked to a particular soteriological methodology, regardless of a surgical outcome, I am not shaken.

This doesn’t mean that hope is passive or merely a form of stoicism or resignation. Hope might be called “active patience,” and one who is hope is one who knows that God is for him or her, in partnership with him or her.

Our preaching must aim to elevate the Mystery Index, the mystery of faith and hope. It must be a sign that we are making ourselves available to others, helping miserable people become mysterious people! That is, people who understand that their constant faith in God is not misplaced. People of faith and hope are people whose hope and faith shall not go unrewarded.

The alternative is despair, which says that there is nothing — really — worth living for. The reward of faith and hope is that, well, yes, there is much in my current and future reality worth living for. And, by God, I am going to do it. I am going to live — in faith and in hope. In mystery.

The idea of a Misery Index has been around for a long time — since the early ’70s. It’s actually an economic bellwether that’s determined by factoring inflation and unemployment. Economists reason that when unemployment and inflation are high, that generally spells misery for consumers.

The current Misery Index (for June 2009) is 8.16.

Yesterday was a particularly “low” day in our worship service. It was cold. Many people were away with all manner of ailments, many related to winter. Others had been on holiday and were ill. Others just stayed home, I’m told, because they just don’t feel like coming out at the moment. We struggled with hymns, Bible reading and Prayers. Many parents with children were absent, so our Sunday School was “light on”. I preached as fervently as I could, but the faces looking back at me seemed blank and bored. I came home to a time of “low prayer” – O Lord help me, I feel as if I have been laid low. (Sort of like a ‘Lamentation’.

How does one preach when people are miserable – and the preacher feels miserable too!. Along with the above “winter stuff” I have people in my congregation who have lost their jobs, maybe they might lose their homes, their retirement packages. They’ve watched their stock portfolios plunge in value, and many are delaying retirement because they simply can’t afford to retire right now. People are struggling to make ends meet. How does one preach in such contexts?

This brings me to the Mystery Index, which is suggested to me by what I remember of Gabriel Marcel’s ruminations on the general subject. How one can keep faith and have hope when utterly miserable has got to be the greatest mystery of all time.

Marcel, a philosopher and playwright, has been dead for more than 25 years now, but he’s still worth a read. Called by some a Christian existentialist, he addresses our subject in his book The Mystery of Being, originally delivered as the Gifford Lectures at Harvard.

Although Marcel doesn’t refer to a Mystery Index, in my thinking the Mystery Index is determined by the factors of faith (what Marcel calls “creative fidelity”) and hope. His ideas about being and having, availability and nonavailability are worth review. He says that too often people talk about trying to “have” this or that, when in fact, it isn’t a question of having something, such as love or hope, but being love and hope. A key component in this mystery is how we relate to others. When we make ourselves available to others, we link ourselves with their world and experience. We are present to them and for them, in communication with them. We are at their disposal when they’re in need. They aren’t alone.

When we are present to others, i.e., available to others, they are enabled, or empowered, to be faith and to be hope in miserable times. The problem with faith is that it must be constant and must have someone or something as its object. While God is the ultimate object of faith, our preaching helps mediate that object.

As for hope, Marcel argues that a person who is hope doesn’t accept the current situation as final. Hope isn’t fixed on any particular method of deliverance. Surgery to remove a cancer, for example, may not produce a desired result. But as a person of hope whose hope isn’t linked to a particular soteriological methodology, regardless of a surgical outcome, I am not shaken.

This doesn’t mean that hope is passive or merely a form of stoicism or resignation. Hope might be called “active patience,” and one who is hope is one who knows that God is for him or her, in partnership with him or her.

Our preaching must aim to elevate the Mystery Index, the mystery of faith and hope. It must be a sign that we are making ourselves available to others, helping miserable people become mysterious people! That is, people who understand that their constant faith in God is not misplaced. People of faith and hope are people whose hope and faith shall not go unrewarded.

The alternative is despair, which says that there is nothing — really — worth living for. The reward of faith and hope is that, well, yes, there is much in my current and future reality worth living for. And, by God, I am going to do it. I am going to live — in faith and in hope. In mystery.

From "In The thick Of It"

‘The church is on the frontline of efforts to tackle poverty: it is at the heart of poor communities

and shares in their suffering. Pastors and congregations are making a real difference as they roll

their sleeves up, get their hands dirty, offer support and bring communities together. In many

contexts only the church can reach the poorest in this way. And the church could do so much more.

The church as a whole needs to wake up to its God-given mandate and potential to tackle poverty

– at home and overseas ...

THE ARCHBISHOP OF YORK, DR JOHN SENTAMU

and shares in their suffering. Pastors and congregations are making a real difference as they roll

their sleeves up, get their hands dirty, offer support and bring communities together. In many

contexts only the church can reach the poorest in this way. And the church could do so much more.

The church as a whole needs to wake up to its God-given mandate and potential to tackle poverty

– at home and overseas ...

THE ARCHBISHOP OF YORK, DR JOHN SENTAMU

Wednesday, 8 July 2009

Whither us at Glenelg

In her book “Christianity for the Rest of Us” Diana Butler Bass makes reference to our future as being bound up with our past. Just recently I’ve been re-reading, being in Glenelg the “birthplace”, as it were, of South Australia, some of the early history of the area but, more importantly, this history of the Glenelg Congregational Church now St. Andrew’s by the Sea Uniting Church.

As a church in the centre of Glenelg St. Andrew’s continues to be a church that each day not only opens its doors, but also its life, to all those who would pass by. And some days they are many indeed. A place to visit, a place to pause, a place to pray on one’s journey from and to.

But the area is changing, not only in its demographics, but in its shopping and recreational life too. We have spoken of ourselves as being “the church in the market place” and “the oldest trader in Jetty Rd and Glenelg”. And so we are. But profound changes are occurring around us and we need to quickly realize that new forms of life as a church are needed of us. What “worked” yesterday may not be the answer to our concerns today. The world about us is new and different. How will we continue to worship, witness and serve in the future? Sure, at times it all seems to be overwhelming, but God still calls us to be faithful people in this context. As Diana Butler Bass says “ .. Christianity is a sacred pathway to someplace better, a journey of transforming ourselves, our faith communities, and our world.”

As a church in the centre of Glenelg St. Andrew’s continues to be a church that each day not only opens its doors, but also its life, to all those who would pass by. And some days they are many indeed. A place to visit, a place to pause, a place to pray on one’s journey from and to.

But the area is changing, not only in its demographics, but in its shopping and recreational life too. We have spoken of ourselves as being “the church in the market place” and “the oldest trader in Jetty Rd and Glenelg”. And so we are. But profound changes are occurring around us and we need to quickly realize that new forms of life as a church are needed of us. What “worked” yesterday may not be the answer to our concerns today. The world about us is new and different. How will we continue to worship, witness and serve in the future? Sure, at times it all seems to be overwhelming, but God still calls us to be faithful people in this context. As Diana Butler Bass says “ .. Christianity is a sacred pathway to someplace better, a journey of transforming ourselves, our faith communities, and our world.”

No wage increase for low paid workers

Felling a bit angry this morning, so a bit of a 'rant'.

Must be hard for Prof. Harper with his knowledge and experience of living on the minimum wage.

Must be hard for Prof. Harper with his knowledge and experience of living on the minimum wage.

Thursday, 18 June 2009

In praise of Non-Conformity

1. We are raised to conform and follow orders, so many of us get to like it.

From our birth, we are surrounded by people telling us what to do: when to eat, when to sleep, what to wear and how to behave. From parents, through other older family members, schoolteachers and anyone in charge of an activity we took part in, there is always someone who claims to know what’s best for us and is ready to make sure we do as we are told.

In fact, one of the earliest lessons we learn is that being loved and assisted by others—an essential requirement for any child—depends pretty much on doing what you are told. When, like all children, we try a little rebellion, we discover punishments can go beyond mere withdrawal of approval on a temporary basis. A small number of people refuse to follow this system, but most find it quickly becomes ‘normal’.

There’s another benefit too: it saves us having to make our own decisions and live by the consequences. By doing what we are told, we can shift responsibility for mistakes onto someone else. The excuse, “I was only following orders” probably began with the person who loaded the Ark and didn’t have the wit to make sure the two houseflies were trodden on by the elephants.

2. We tend to trust what the biggest crowd says is right

You would think we should have realized long before now that fashion is an extremely poor guide to sensible living, but no; we still rush to jump into every type of nonsense, rather than risk feeling left out. If the current recession should cause people to re-assess any of their beliefs, it is surely this one. Every cycle of boom and bust arises directly from the tendency people have to follow a crowd. There’s a famous book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. It was written by Charles Mackay (1841-1889) and quickly became the classic work on popular manias of all kinds, financial and otherwise. If you haven’t already, read it.

Democracy may be based on following the wishes of the majority, but that is not a good guide in other areas of life. The government of a country needs to be based on making sure minorities and individuals, be they rich aristocrats or party members, can’t hi-jack the levers of power for their own purposes. In most of our personal life, we shouldn’t want to be part of the majority—we should want to stand out in some way.

3. We put far too much trust in ‘experts’ and authority figures

Nice, respectable people—like everyone who reads this article, naturally—don’t question authority or cause trouble. That’s why we do what officials of all kinds tell us to, from the police to the tax man. We are also brought up to respect obvious ‘experts’ like doctors (never mind that many are paid by drug companies to prescribe specific drugs or write papers proving they work), lawyers (who are never, of course, motivated by sordid motives like money), pastors and the clergy (I’ll say no more) and even media types and self-appointed gurus.

This deference to authority quickly spills over to include almost anyone who seems to know what they doing when we don’t. We therefore trusted bankers, mortgage ‘experts’ and financial advisers to look after our money. Look where that got us.

4. We are nearly all creatures of habit

Why do people buy the same brand for decades, despite evidence it costs more than it should and is no better than any of the others—even worse? Why do people drive to work by more or less the same route, at the same time, each day? Why do they watch the same TV channels, take the same type of vacation and spend their weekends doing the same things?

Why do organizations persist with products long after they have started to lose market share? Or follow approaches to management that have been in place for decades? Or refuse to change the way they operate until competitors force them to?

People frequently know what they are doing isn’t effective, healthy, logical, or even remotely sensible, yet they still do it. Why? It feels comfortable. They’re used to doing it that way. That’s the way things are done around here. Besides, many are terrified of change—usually because they’ve never done it except in the most dire emergency.

If you don’t use a muscle for years, or ever, then suddenly do something that demands you put some strain on it, it’s going to hurt badly. If you never change willingly, it will hurt terribly when you do. In both cases, it’s not the new activity that is the problem; it’s the total lack of use that went before.

Why you shouldn’t conform for the sake of it

* Making up your own mind ‘exercises’ your mental muscles, keeps your mind fit and encourages you to stay abreast of events. If you need any of those facilities (and you will), it’s better to keep them in trim than suddenly find they’re too rusty to work.

* There’s really no evidence that anyone knows what is right for you better than you do. After all, you’re the only one who knows what is going on inside your head and what matters to you most.

* Nearly everyone who is eager to tell you what to do is coming from their agenda, not yours. They want you to do what suits them. You probably ought to do what suits you.

* Following fashion and obeying orders without question leaves you wide open to manipulation and fraud.

* If you want to get on in life and do something important, you won’t do either by being like everyone else. The word ‘mediocre’ comes from the Latin word ‘medius’, meaning ‘in the middle’. No one ever stood out by fitting in.

* Being a conformist blocks any change until it’s too late to change easily or in your own time. Conformists go through life experiencing periods of monotony, interspersed with crises when they frantically try to find some one to tell them what to do as their world crashes around their ears.

* Organizations that follow ‘industry best practice’, benchmarking and other mechanistic ways of making sure they stay with the crowd, lay themselves wide open to being wrong-footed by any competitor willing to do something new and different.

If we learn nothing else from our recent brush with economic chaos and disaster it should be this: do what everyone else does and you’ll end up where everyone else is—in the ditch on the side of the road, watching the tail lights of the new leaders speeding into the distance.

(Sent to me from a friend who found this on "Slow Leadership")

From our birth, we are surrounded by people telling us what to do: when to eat, when to sleep, what to wear and how to behave. From parents, through other older family members, schoolteachers and anyone in charge of an activity we took part in, there is always someone who claims to know what’s best for us and is ready to make sure we do as we are told.

In fact, one of the earliest lessons we learn is that being loved and assisted by others—an essential requirement for any child—depends pretty much on doing what you are told. When, like all children, we try a little rebellion, we discover punishments can go beyond mere withdrawal of approval on a temporary basis. A small number of people refuse to follow this system, but most find it quickly becomes ‘normal’.

There’s another benefit too: it saves us having to make our own decisions and live by the consequences. By doing what we are told, we can shift responsibility for mistakes onto someone else. The excuse, “I was only following orders” probably began with the person who loaded the Ark and didn’t have the wit to make sure the two houseflies were trodden on by the elephants.

2. We tend to trust what the biggest crowd says is right

You would think we should have realized long before now that fashion is an extremely poor guide to sensible living, but no; we still rush to jump into every type of nonsense, rather than risk feeling left out. If the current recession should cause people to re-assess any of their beliefs, it is surely this one. Every cycle of boom and bust arises directly from the tendency people have to follow a crowd. There’s a famous book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. It was written by Charles Mackay (1841-1889) and quickly became the classic work on popular manias of all kinds, financial and otherwise. If you haven’t already, read it.

Democracy may be based on following the wishes of the majority, but that is not a good guide in other areas of life. The government of a country needs to be based on making sure minorities and individuals, be they rich aristocrats or party members, can’t hi-jack the levers of power for their own purposes. In most of our personal life, we shouldn’t want to be part of the majority—we should want to stand out in some way.

3. We put far too much trust in ‘experts’ and authority figures

Nice, respectable people—like everyone who reads this article, naturally—don’t question authority or cause trouble. That’s why we do what officials of all kinds tell us to, from the police to the tax man. We are also brought up to respect obvious ‘experts’ like doctors (never mind that many are paid by drug companies to prescribe specific drugs or write papers proving they work), lawyers (who are never, of course, motivated by sordid motives like money), pastors and the clergy (I’ll say no more) and even media types and self-appointed gurus.

This deference to authority quickly spills over to include almost anyone who seems to know what they doing when we don’t. We therefore trusted bankers, mortgage ‘experts’ and financial advisers to look after our money. Look where that got us.

4. We are nearly all creatures of habit

Why do people buy the same brand for decades, despite evidence it costs more than it should and is no better than any of the others—even worse? Why do people drive to work by more or less the same route, at the same time, each day? Why do they watch the same TV channels, take the same type of vacation and spend their weekends doing the same things?

Why do organizations persist with products long after they have started to lose market share? Or follow approaches to management that have been in place for decades? Or refuse to change the way they operate until competitors force them to?

People frequently know what they are doing isn’t effective, healthy, logical, or even remotely sensible, yet they still do it. Why? It feels comfortable. They’re used to doing it that way. That’s the way things are done around here. Besides, many are terrified of change—usually because they’ve never done it except in the most dire emergency.

If you don’t use a muscle for years, or ever, then suddenly do something that demands you put some strain on it, it’s going to hurt badly. If you never change willingly, it will hurt terribly when you do. In both cases, it’s not the new activity that is the problem; it’s the total lack of use that went before.

Why you shouldn’t conform for the sake of it

* Making up your own mind ‘exercises’ your mental muscles, keeps your mind fit and encourages you to stay abreast of events. If you need any of those facilities (and you will), it’s better to keep them in trim than suddenly find they’re too rusty to work.

* There’s really no evidence that anyone knows what is right for you better than you do. After all, you’re the only one who knows what is going on inside your head and what matters to you most.

* Nearly everyone who is eager to tell you what to do is coming from their agenda, not yours. They want you to do what suits them. You probably ought to do what suits you.

* Following fashion and obeying orders without question leaves you wide open to manipulation and fraud.

* If you want to get on in life and do something important, you won’t do either by being like everyone else. The word ‘mediocre’ comes from the Latin word ‘medius’, meaning ‘in the middle’. No one ever stood out by fitting in.

* Being a conformist blocks any change until it’s too late to change easily or in your own time. Conformists go through life experiencing periods of monotony, interspersed with crises when they frantically try to find some one to tell them what to do as their world crashes around their ears.

* Organizations that follow ‘industry best practice’, benchmarking and other mechanistic ways of making sure they stay with the crowd, lay themselves wide open to being wrong-footed by any competitor willing to do something new and different.

If we learn nothing else from our recent brush with economic chaos and disaster it should be this: do what everyone else does and you’ll end up where everyone else is—in the ditch on the side of the road, watching the tail lights of the new leaders speeding into the distance.

(Sent to me from a friend who found this on "Slow Leadership")

Vulnerability

When someone who has no need to be vulnerable becomes vulnerable in order to identify with those that are, and together with them struggles to be resilient against all death dealing forces, structures and systems, and thus together with them moves towards a society transformed—of justice, and communion , then he or she participates in the vulnerable mission of God. The kind of mission that is required here is not of contemplative theologizing but liberative action in solidarity with the oppressed. It is a solidarity that is built on a relationship of complete vulnerability and identification with the oppressed community; sustained by a process of mutual giving and receiving, and nurtured by seeing in the other the ethical demand of responsibility.

(from an Indian missiologist)

(from an Indian missiologist)

Wednesday, 17 June 2009

"What would've happened if ..?"

Twenty years ago, we were actively pushing our young people out the doors of our churches and Dioceses. We didn’t mean to – it’s just that we wouldn’t make room for them in our activities; we didn’t include their voices in our public conversations; we didn’t ask them for stories of their encounters with the good news of God as known in Jesus Christ. As a result, we lost them. They went elsewhere to find expression for their gifts. Today, there is little likelihood of attracting them back into our Church. In their absence, we lost sight of the huge gap growing between the insider language of the Church and the realities of the Culture we are called to serve. Now that’s a huge loss, but it’s not the biggest loss we’ve experienced, subsequently.

The greater loss is that we forgot how to nurture the prophetic voice in our midst. We’ve forgotten how to foster new young leaders in nurturing and mutually-shaping communities. Today, we are working on bringing new young leaders into our churches but that’s not the same as nurturing the prophetic voice in community – training new leaders to cultivate community with a hoe instead of directing with the Verger’s mace. That takes time to develop! It’s an art of “being in community” that very few have ever experienced, nonetheless mastered.

So, (several of them concurred) if we could go back – if you could learn from us – we would encourage you to take action now; do not wait until you have it figured out. Invite faith-filled young leaders into your communities. Listen. Try on new ideas. Experiment. Be willing to fail – often and early. “Fail away” until patterns of meaning start to emerge from your communities in discernment. Listen for the Fresh Expressions of the Spirit in their sometimes awkward and clumsy offerings. Especially listen and observe the way they use ritual and music to make sense of the insanity of our lives.

Episcopal priest's blog - don't have info.

The greater loss is that we forgot how to nurture the prophetic voice in our midst. We’ve forgotten how to foster new young leaders in nurturing and mutually-shaping communities. Today, we are working on bringing new young leaders into our churches but that’s not the same as nurturing the prophetic voice in community – training new leaders to cultivate community with a hoe instead of directing with the Verger’s mace. That takes time to develop! It’s an art of “being in community” that very few have ever experienced, nonetheless mastered.

So, (several of them concurred) if we could go back – if you could learn from us – we would encourage you to take action now; do not wait until you have it figured out. Invite faith-filled young leaders into your communities. Listen. Try on new ideas. Experiment. Be willing to fail – often and early. “Fail away” until patterns of meaning start to emerge from your communities in discernment. Listen for the Fresh Expressions of the Spirit in their sometimes awkward and clumsy offerings. Especially listen and observe the way they use ritual and music to make sense of the insanity of our lives.

Episcopal priest's blog - don't have info.

Tuesday, 2 June 2009

Inculturation

Our lack of inculturation has fostered both the alienation of some Christians and an over ready willingness of others to live in two different cultures, one of their religion and and the other of their everyday life. Other Christians again have left our churches because of this cultural insensitivity. Similarly non Christians have found the foreignness of the church a great barrier to faith...

...True inculturation implies a willingness in worship to listen to culture.... it has to make contact with the deep feelings of people. It can only be achieved through an openness to innovation and experimentation, an encouragement of local creativity, and a readiness to reflect critically at every stage of the process, a process which in principle is never ending.

...True inculturation implies a willingness in worship to listen to culture.... it has to make contact with the deep feelings of people. It can only be achieved through an openness to innovation and experimentation, an encouragement of local creativity, and a readiness to reflect critically at every stage of the process, a process which in principle is never ending.

Wednesday, 27 May 2009

Delusional Optimism'

(Forwarded on from a friend)

‘Delusional optimism’ is a habitual failure to accept reality, unless it matches the positive outcome you want. Like Positive Thinking, it’s a way of trying to fool your mind into seeing something ‘good’ instead of whatever is actually there. It’s imposing your own standards of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ on events, which have no such qualities: they are what they are. As William Shakespeare wrote: “It is neither good nor bad, but thinking makes it so.” In this case, our own thinking, which may be confused, poorly informed or simply wishful.

Delusional optimism causes people to either ignore or down-play risk, and so becomes an additional risk factor in its own right. Russell Ackoff, in Management in Small Doses wrote : “The cost of preparing for critical events that do not occur is generally very small in comparison to the cost of being unprepared for those that do.”

Like the nonsense peddled as the ‘Law of Attraction’, delusional optimism works by persuading people that wishing for something hard enough will magically cause it to happen; or that staying positive will, equally magically, prevent bad things coming along.

It would be nice to be able to work magic, but the only kind that exists in our world is the kind you see on the stage; and that takes hard work, years of practice and is based on deluding the audience into seeing what you tell them to see, not what is actually happening.

Refusing to give up

Another element in delusional optimism is a dogged refusal to give up. This also seems more revered in the USA than elsewhere in the world. It too causes unnecessary pain and loss as people go on pouring time, effort and resources into projects that ‘died’ long ago.

Why it’s better to expect failure before you begin—then keep trying just the same

Failure is a part of everyday reality. You try things and sometimes you succeed, sometimes you fail. It’s extremely unlikely that you will succeed in everything you do, and equally unlikely that you will fail. Life is a mixture. Sometimes up, sometimes down.

If you expect some failure before you begin, you can plan for it. It won’t take you by surprise. You don’t, of course, expect to fail at everything—that is as irrational as expecting to succeed all the time—but you do expect that some things won’t turn out as you want them to.

“Pessimism is, in brief, playing the sure game. You cannot lose at it; you may gain. It is the only view of life in which you can never be disappointed. Having reckoned what to do in the worst possible circumstances, when better arise, as they may, life becomes child’s play.” ~ Thomas Hardy

Creating realistic expectations

Many people have pointed out that a good deal of the trouble we have all gone through in the past few months has been caused by organizations and bosses setting up completely unrealistic expectations. By claiming to be able to deliver endless growth in profits, they produced no profits at all.

We do exactly the same to ourselves. Puffed up with delusional optimism, we fill our minds with expectations we will never be able to fulfill. If we had been realistic, the goals we set ourselves would, for the most part, have been fulfilled. Our failures would have been offset by our successes.

Instead, we set ourselves up for continual failure, not because of lack of ability, but because our expectations allowed for no failure at all. By being determined to have it all, we spoiled our pleasure in what we did have. By avoiding the extreme of delusional optimism with an occasional touch of pessimism, you’ll find realism—the middle ground. That never hurt anyone.

Pessimists make back-ups. Optimists believe they’ll never lose their data.

‘Delusional optimism’ is a habitual failure to accept reality, unless it matches the positive outcome you want. Like Positive Thinking, it’s a way of trying to fool your mind into seeing something ‘good’ instead of whatever is actually there. It’s imposing your own standards of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ on events, which have no such qualities: they are what they are. As William Shakespeare wrote: “It is neither good nor bad, but thinking makes it so.” In this case, our own thinking, which may be confused, poorly informed or simply wishful.

Delusional optimism causes people to either ignore or down-play risk, and so becomes an additional risk factor in its own right. Russell Ackoff, in Management in Small Doses wrote : “The cost of preparing for critical events that do not occur is generally very small in comparison to the cost of being unprepared for those that do.”

Like the nonsense peddled as the ‘Law of Attraction’, delusional optimism works by persuading people that wishing for something hard enough will magically cause it to happen; or that staying positive will, equally magically, prevent bad things coming along.

It would be nice to be able to work magic, but the only kind that exists in our world is the kind you see on the stage; and that takes hard work, years of practice and is based on deluding the audience into seeing what you tell them to see, not what is actually happening.

Refusing to give up

Another element in delusional optimism is a dogged refusal to give up. This also seems more revered in the USA than elsewhere in the world. It too causes unnecessary pain and loss as people go on pouring time, effort and resources into projects that ‘died’ long ago.

Why it’s better to expect failure before you begin—then keep trying just the same

Failure is a part of everyday reality. You try things and sometimes you succeed, sometimes you fail. It’s extremely unlikely that you will succeed in everything you do, and equally unlikely that you will fail. Life is a mixture. Sometimes up, sometimes down.

If you expect some failure before you begin, you can plan for it. It won’t take you by surprise. You don’t, of course, expect to fail at everything—that is as irrational as expecting to succeed all the time—but you do expect that some things won’t turn out as you want them to.

“Pessimism is, in brief, playing the sure game. You cannot lose at it; you may gain. It is the only view of life in which you can never be disappointed. Having reckoned what to do in the worst possible circumstances, when better arise, as they may, life becomes child’s play.” ~ Thomas Hardy

Creating realistic expectations

Many people have pointed out that a good deal of the trouble we have all gone through in the past few months has been caused by organizations and bosses setting up completely unrealistic expectations. By claiming to be able to deliver endless growth in profits, they produced no profits at all.

We do exactly the same to ourselves. Puffed up with delusional optimism, we fill our minds with expectations we will never be able to fulfill. If we had been realistic, the goals we set ourselves would, for the most part, have been fulfilled. Our failures would have been offset by our successes.

Instead, we set ourselves up for continual failure, not because of lack of ability, but because our expectations allowed for no failure at all. By being determined to have it all, we spoiled our pleasure in what we did have. By avoiding the extreme of delusional optimism with an occasional touch of pessimism, you’ll find realism—the middle ground. That never hurt anyone.

Pessimists make back-ups. Optimists believe they’ll never lose their data.

Monday, 27 April 2009

The loss of childhood wonder

As a young child, each of us was curious—the consummate explorer. We were open to the new, the magical, the aliveness and the wonder of life. We had no settled mis-perceptions, no mis-conceptions of reality, no expectations or paradigms to limit or prescribe our view of the world. Just curiosity and wonderment.

As we get older, all that stops. We are taught how to think and act in ways that are ‘appropriate’ for our age and the society in which we live. The fortunate ones subvert the brainwashing and find ways to allow their curiosity and wonderment to thrive. All the rest give in and allow their curiosity and sense of adventure to wither away. As Albert Einstein said, “It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.”

As we grow older still, we fall easily into habitual ways of living. We grow tired and slip into the comfort of a routine. We no longer choose to take risks, to look beyond the immediate and step off the well-worn path of the ‘tried and true’, the familiar, the comfortable, the safe. Ours is a culture rife with boredom: lots of repetitive activity, little curiosity. What there is in the way of curiosity is blocked by hubris—that obsessive pride based on an “I know it all” approach to life that closes down the imagination, stifles innovation and leaves us always where we have already been.

As we get older, all that stops. We are taught how to think and act in ways that are ‘appropriate’ for our age and the society in which we live. The fortunate ones subvert the brainwashing and find ways to allow their curiosity and wonderment to thrive. All the rest give in and allow their curiosity and sense of adventure to wither away. As Albert Einstein said, “It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.”

As we grow older still, we fall easily into habitual ways of living. We grow tired and slip into the comfort of a routine. We no longer choose to take risks, to look beyond the immediate and step off the well-worn path of the ‘tried and true’, the familiar, the comfortable, the safe. Ours is a culture rife with boredom: lots of repetitive activity, little curiosity. What there is in the way of curiosity is blocked by hubris—that obsessive pride based on an “I know it all” approach to life that closes down the imagination, stifles innovation and leaves us always where we have already been.

Friday, 24 April 2009

The Language of Leadership

Listen carefully. Your manager is telling you how he or she sees your relationship. What we call things tells the world the hidden truth about how we think. In the world of work, the language leaders use to describe their subordinates reveals the true nature of the relationship between them—the hidden dynamic underneath any surface politeness.

Why do some leaders describe the corporation as a family? Why do others use sporting terms (“We’re a tightly-knit team”); or military jargon (“This is D-Day. We need maximum effort from everyone”); or even religious terms (“I want everyone singing from the same hymn-sheet”)?

I don’t think it’s chance. What’s in your mind unconsciously expresses itself in the words you use—something Sigmund Freud pointed to many years ago that has passed into the language as the term ‘Freudian slip’.

Some more examples of significant leadership terminology

• Macho language and sayings come naturally to macho leaders. You often hear them talking about subordinates who “can’t stand the heat” or describing their own role as “kicking butt.” They love winning, in any forum, so they slip just as easily into the terms you would expect of any ultra-competitive situation: “winning is all that matters,” “I’m only interested in results,” or “he (or she) was never a contender.”

• Command-and-control autocrats love to use fighting terminology. If you hear expressions like “being in a fire-fight,” “taking out the bad guys,” or the need to “come out swinging,” you know you have a leader whose mind sees the world as a series of fights to be won and enemies to be vanquished. To natural fighters, winners are heroes, losers are beneath contempt.

• Speed freaks betray their obsession in rapid delivery and characteristic language. They constantly urge those around them to “cut to the chase,” “hit the ground running,” “give me the bottom line,” or “expedite” things. Nothing annoys a speed freak more than being asked to be patient or take time out to listen when there is action to be attended to.

• ‘Greed freaks’ always want to talk about money and rewards. They want to know “where the leverage is” and “what’s in it for me?” They demand to be told the benefits before they will listen to anything else. Discussion bores them, but they will spend hours poring over spreadsheets and projections. They also expect everyone else to be motivated solely by cash and are bewildered when they encounter anyone who is not.

• Habitual talk of teams, liberally laced with sporting terms and analogies, reveals the leader who sees him or herself as somewhere between team captain and coach. That gives the leader license to bully or weed out ‘weak links’ in the team, throw tantrums on the sideline, shout out playing instructions all the time, expect everyone to accept that he or she knows the game better than they do, and determine the ‘game strategy’ the whole team will follow without question.

• Patriarchs (and matriarchs) describe the rest of the organization as a ‘family’ and handle them accordingly. Like genuine family relationships, this can be two-edged. For every set of loving, caring and supporting ‘parents’, there will be the demanding and dysfunctional ones who try to control every aspect of family life, use guilt as a weapon, demand obedience at all times and treat unapproved behavior as the tantrums of naughty children, to be punished ‘for their own good’. Few people can be as simultaneously cruel and sanctimonious as a domineering parent.

Habitual patterns of language reveal any leader’s assumptions and their attitudes to the supervisory relationship. What you say shows how you think. How you think determines what you do.

Since these relationships are inevitably reciprocal, macho leaders demand timid, compliant followers. To a macho leader, anyone who won’t be led is a rival and a threat. Patriarchal leaders need to see themselves as the ‘fathers’ of a business ‘family’, so anyone who opposes them is going to be treated like a naughty, rebellious child in need of a healthy dose of discipline. Autocrats need disciplined followers who react to orders with a salute and cheerfully sacrifice themselves when called upon to do so.

Why do some leaders describe the corporation as a family? Why do others use sporting terms (“We’re a tightly-knit team”); or military jargon (“This is D-Day. We need maximum effort from everyone”); or even religious terms (“I want everyone singing from the same hymn-sheet”)?

I don’t think it’s chance. What’s in your mind unconsciously expresses itself in the words you use—something Sigmund Freud pointed to many years ago that has passed into the language as the term ‘Freudian slip’.

Some more examples of significant leadership terminology

• Macho language and sayings come naturally to macho leaders. You often hear them talking about subordinates who “can’t stand the heat” or describing their own role as “kicking butt.” They love winning, in any forum, so they slip just as easily into the terms you would expect of any ultra-competitive situation: “winning is all that matters,” “I’m only interested in results,” or “he (or she) was never a contender.”

• Command-and-control autocrats love to use fighting terminology. If you hear expressions like “being in a fire-fight,” “taking out the bad guys,” or the need to “come out swinging,” you know you have a leader whose mind sees the world as a series of fights to be won and enemies to be vanquished. To natural fighters, winners are heroes, losers are beneath contempt.

• Speed freaks betray their obsession in rapid delivery and characteristic language. They constantly urge those around them to “cut to the chase,” “hit the ground running,” “give me the bottom line,” or “expedite” things. Nothing annoys a speed freak more than being asked to be patient or take time out to listen when there is action to be attended to.

• ‘Greed freaks’ always want to talk about money and rewards. They want to know “where the leverage is” and “what’s in it for me?” They demand to be told the benefits before they will listen to anything else. Discussion bores them, but they will spend hours poring over spreadsheets and projections. They also expect everyone else to be motivated solely by cash and are bewildered when they encounter anyone who is not.

• Habitual talk of teams, liberally laced with sporting terms and analogies, reveals the leader who sees him or herself as somewhere between team captain and coach. That gives the leader license to bully or weed out ‘weak links’ in the team, throw tantrums on the sideline, shout out playing instructions all the time, expect everyone to accept that he or she knows the game better than they do, and determine the ‘game strategy’ the whole team will follow without question.

• Patriarchs (and matriarchs) describe the rest of the organization as a ‘family’ and handle them accordingly. Like genuine family relationships, this can be two-edged. For every set of loving, caring and supporting ‘parents’, there will be the demanding and dysfunctional ones who try to control every aspect of family life, use guilt as a weapon, demand obedience at all times and treat unapproved behavior as the tantrums of naughty children, to be punished ‘for their own good’. Few people can be as simultaneously cruel and sanctimonious as a domineering parent.

Habitual patterns of language reveal any leader’s assumptions and their attitudes to the supervisory relationship. What you say shows how you think. How you think determines what you do.

Since these relationships are inevitably reciprocal, macho leaders demand timid, compliant followers. To a macho leader, anyone who won’t be led is a rival and a threat. Patriarchal leaders need to see themselves as the ‘fathers’ of a business ‘family’, so anyone who opposes them is going to be treated like a naughty, rebellious child in need of a healthy dose of discipline. Autocrats need disciplined followers who react to orders with a salute and cheerfully sacrifice themselves when called upon to do so.

Thursday, 26 March 2009

Wednesday, 25 March 2009

What organizations and leaders claim they do

(The Merchant Mindset )

Value initiative and enterprise

Accept dissent as a way to improve things

Act honestly and respect contracts

Avoid force in favor of voluntary agreements

Stay open to new ideas

Collaborate easily with others

Seek open competition

Reward efficiency, thrift and industriousness

Stay optimistic

Use incentives linked to specific outcomes

What many of them actually do

(The Guardian Mindset)

Value discipline and obedience

Require loyalty and extract vengeance

Accept deception for the sake of getting the job done

Reject trade-offs and use force to gain desired ends

Value tradition

Protect exclusivity and treat strangers with suspicion

Seek opportunities to display personal prowess

Be ostentatious and protect honor

Be fatalistic

Dispense largess and patronage

Value initiative and enterprise

Accept dissent as a way to improve things

Act honestly and respect contracts

Avoid force in favor of voluntary agreements

Stay open to new ideas

Collaborate easily with others

Seek open competition

Reward efficiency, thrift and industriousness

Stay optimistic

Use incentives linked to specific outcomes

What many of them actually do

(The Guardian Mindset)

Value discipline and obedience

Require loyalty and extract vengeance

Accept deception for the sake of getting the job done

Reject trade-offs and use force to gain desired ends

Value tradition

Protect exclusivity and treat strangers with suspicion

Seek opportunities to display personal prowess

Be ostentatious and protect honor

Be fatalistic

Dispense largess and patronage

Emerging is ...

A FANTASTIC PIECE FROM JONNY BAKER'S BLOG

Christian communities that emerge out of very particular cultural contexts where the traditional church is basically irrelevant. These cultural contexts are more often than not urban, youngish, and post-modern.

Emerging church is not a worship style. I know emerging churches that do traditional liturgy with jazz (Mercy Seat), who use electronica (Church of the Beloved), who are a capella Gregorian chant (House for All Sinners and Saints), and who do nothing but old-time Southern gospel (House of Mercy).

So, when traditional churches in the suburbs are wanting to attract young people (with all the good intentions in the world) and they ape some kind of worship style they read about in a Zondervan book by starting an “emerging” worship service, it’s a bit … ironic.

There is nothing ideal about these communities. Yes, we need more generational diversity. And yes, we have the same number of issues and problems as other churches. All I know is that about 95% of the people who come to my church were not actually going to any church at all when they joined us.

Okay, now before you leave me angry responses let me say that this is not saying there is something wrong with the traditional church. Traditional church is often a faithful expression of Christian community. But people in my scene would have to culturally commute from who they are to who the traditional church is.

Christian communities that emerge out of very particular cultural contexts where the traditional church is basically irrelevant. These cultural contexts are more often than not urban, youngish, and post-modern.

Emerging church is not a worship style. I know emerging churches that do traditional liturgy with jazz (Mercy Seat), who use electronica (Church of the Beloved), who are a capella Gregorian chant (House for All Sinners and Saints), and who do nothing but old-time Southern gospel (House of Mercy).

So, when traditional churches in the suburbs are wanting to attract young people (with all the good intentions in the world) and they ape some kind of worship style they read about in a Zondervan book by starting an “emerging” worship service, it’s a bit … ironic.

There is nothing ideal about these communities. Yes, we need more generational diversity. And yes, we have the same number of issues and problems as other churches. All I know is that about 95% of the people who come to my church were not actually going to any church at all when they joined us.

Okay, now before you leave me angry responses let me say that this is not saying there is something wrong with the traditional church. Traditional church is often a faithful expression of Christian community. But people in my scene would have to culturally commute from who they are to who the traditional church is.

Tuesday, 24 March 2009

Efforts at change

(from an Intro to a Alan Hirsch article. Worthy of thought!)

One of the foremost signs of present-day society is the presence of increasingly complex systems that permeate just about every aspect of our lives. The admiration we feel in contemplating the wonders of new technologies is tinged by an increasing sense of uneasiness, if not outright discomfort. Though these complex systems are hailed for their growing sophistication, there is a increasing recognition that they have also ushered in a social, commercial, and organizational environment that is almost unrecognizable from the perspective of standard church leadership theory and practice.

Although we often hear about successful attempts to revitalize existing churches, the overall track record is very poor. Ministers report again and again that their efforts at organizational change did not yield the promised results. Instead of managing new, revitalized, organizations, they ended up managing the unwanted side effects of their efforts. At first glance, this situation seems paradoxical. When we observe our natural environment, we see continuous change, adaptation, and creativity; yet our

One of the foremost signs of present-day society is the presence of increasingly complex systems that permeate just about every aspect of our lives. The admiration we feel in contemplating the wonders of new technologies is tinged by an increasing sense of uneasiness, if not outright discomfort. Though these complex systems are hailed for their growing sophistication, there is a increasing recognition that they have also ushered in a social, commercial, and organizational environment that is almost unrecognizable from the perspective of standard church leadership theory and practice.

Although we often hear about successful attempts to revitalize existing churches, the overall track record is very poor. Ministers report again and again that their efforts at organizational change did not yield the promised results. Instead of managing new, revitalized, organizations, they ended up managing the unwanted side effects of their efforts. At first glance, this situation seems paradoxical. When we observe our natural environment, we see continuous change, adaptation, and creativity; yet our

Monday, 16 March 2009

Little fish, little pond

(And it came to pass by me ..)

Many of us spend time and energy trying to convince ourselves, and others, that we are big fish in small ponds or even bigger fish in larger ponds. The reality is we are little fish in little ponds, spending our lives with no idea what may be beyond our immediate experience or long-held beliefs. Most often, we are unable to even consider the possibility of there being another ‘reality’ (pond) out there.

Why don’t you venture out to see if there is a larger pond? Maybe because you feel content, secure and in control in your little pond (or you think you are)? Maybe you’re obsessed with trying to make your pond work for you and are intimidated by the unknown? Maybe you tell yourself you have no interest in exploring anything beyond what you know already?

I suspect most people fall into reason number two: they fear the unknown and feelings of separation from what gives them a (mostly false) sense of security. In their small ponds, they try to create a life of order and control, all the while experiencing stress, anxiety and insecurity.

Why not try a different pond?

What would it be like to venture into a different pond? To give up the need to be in control and swim outside the safe boundaries of the familiar?

What if you were to leave behind your life preservers—ego, beliefs, preconceptions and habitual judgments—and swim into a new pond with an open mind and an open heart? Could you trust that you won’t drown or lose your way?

The deal is this. You can’t think your way into a new pond. You have to let go and dive in. You have to take the risk.

Would you try?

Would you be willing to experience a new pond to find greater well being, fresh possibilities and a new sense of groundedness? If so, the first step is to explore your little pond, taking stock of your habits, beliefs, addictions and self-limiting thoughts. What are you, a little fish in this little pond, attached to and obsessive about? What drives you to want the sense of control and security you try to get from staying with what you know?

Once you uncover what drives you, and choose to let go of your ego needs to control and possess, you are on your way to transforming into a trusting fish that is ready to swim into another pond; a pond where your sense of identity can come from a deeper place, not just your limited mind and ego.

Could you swim with your eyes open?

In this new pond, you’ll need to swim with greater consciousness, always alert and awake. You will need to accept your vulnerability and stay away from self-destructive beliefs, illusions and fantasies. You will need to

trust and let go of dogmatic thoughts and beliefs. You will need to be open to change; to reconsider re-prioritizing your goals so they truly support your balance and well-being (not just your ego).

Moving to a new pond means allowing your ‘neutral mind’ to stay clear from being muddied by worry, goals, judgments, invidious comparisons and constant chatter. This new pond of clear water is still, peaceful and relaxed. You can be open to new experiences. You can be mentally and emotionally at peace, just so long as you keep it free from mud and scum.

Consider this. There is no bigger pond, no better pond—just one pond, where we can all swim in the stillness of the moment, free from the hustle and bustle and nagging of our ego-driven concerns. All it takes is to let yourself go there.

Many of us spend time and energy trying to convince ourselves, and others, that we are big fish in small ponds or even bigger fish in larger ponds. The reality is we are little fish in little ponds, spending our lives with no idea what may be beyond our immediate experience or long-held beliefs. Most often, we are unable to even consider the possibility of there being another ‘reality’ (pond) out there.

Why don’t you venture out to see if there is a larger pond? Maybe because you feel content, secure and in control in your little pond (or you think you are)? Maybe you’re obsessed with trying to make your pond work for you and are intimidated by the unknown? Maybe you tell yourself you have no interest in exploring anything beyond what you know already?

I suspect most people fall into reason number two: they fear the unknown and feelings of separation from what gives them a (mostly false) sense of security. In their small ponds, they try to create a life of order and control, all the while experiencing stress, anxiety and insecurity.

Why not try a different pond?

What would it be like to venture into a different pond? To give up the need to be in control and swim outside the safe boundaries of the familiar?

What if you were to leave behind your life preservers—ego, beliefs, preconceptions and habitual judgments—and swim into a new pond with an open mind and an open heart? Could you trust that you won’t drown or lose your way?

The deal is this. You can’t think your way into a new pond. You have to let go and dive in. You have to take the risk.

Would you try?

Would you be willing to experience a new pond to find greater well being, fresh possibilities and a new sense of groundedness? If so, the first step is to explore your little pond, taking stock of your habits, beliefs, addictions and self-limiting thoughts. What are you, a little fish in this little pond, attached to and obsessive about? What drives you to want the sense of control and security you try to get from staying with what you know?

Once you uncover what drives you, and choose to let go of your ego needs to control and possess, you are on your way to transforming into a trusting fish that is ready to swim into another pond; a pond where your sense of identity can come from a deeper place, not just your limited mind and ego.

Could you swim with your eyes open?

In this new pond, you’ll need to swim with greater consciousness, always alert and awake. You will need to accept your vulnerability and stay away from self-destructive beliefs, illusions and fantasies. You will need to

trust and let go of dogmatic thoughts and beliefs. You will need to be open to change; to reconsider re-prioritizing your goals so they truly support your balance and well-being (not just your ego).

Moving to a new pond means allowing your ‘neutral mind’ to stay clear from being muddied by worry, goals, judgments, invidious comparisons and constant chatter. This new pond of clear water is still, peaceful and relaxed. You can be open to new experiences. You can be mentally and emotionally at peace, just so long as you keep it free from mud and scum.

Consider this. There is no bigger pond, no better pond—just one pond, where we can all swim in the stillness of the moment, free from the hustle and bustle and nagging of our ego-driven concerns. All it takes is to let yourself go there.

Wednesday, 25 February 2009

Wednesday, 18 February 2009

Reflecting on Growth

Are growth and survival always such good ideas?

It's common for people to assume that growth is something essential to every career and organization. I wonder if that's really the case. It's easy to make simplistic statements like “You're either growing or dying”, but isn’t that logical nonsense, based on seeing inanimate objects like organizations as animals? Even animals reach a state of maturity when they no longer grow. And is death always worse than the alternative?

When you think about it more clearly, why shouldn’t organizations die? They have a time when they grow, flourish and fit their environments; then that time is over and they should make way for something else. Prolonging them as they are today by huge infusions of cash isn’t going to change that.

Careers too. Many people find that something is exciting and new for a time, then successful and enjoyable (but essentially stable) for a period, then begins to show signs of aging and incipient failure. Isn’t it best to recognize this, let it go and move on to something different? Why should clinging to a job you now dislike be praiseworthy?

If we want to be realistic about our world (and few people do, much preferring comforting fantasies), we ought to admit that everything—organizations, careers, products, ideas—has a natural life span: some long and some very short. Understanding this natural duration, and where we are within it, is the essential basis for sensible choices.

During the growth period, you may need to make exceptional investments of time or resources to aid that growth. Once established, you need to focus instead on keeping going during a period of maturity. And when it’s time to let go and allow things to pass away to make room for the new, you need to change your actions accordingly.

What I see all the time are futile attempts either to prolong the growth period indefinitely or prevent even the most merciful death. The period of maturity—the period when you should expect to enjoy the benefits from all the effort made during growth—is ignored. Maybe people think it’s too dull.

The fashion today is not just to live for ever, but to be young for ever. If ever there was a departure from reality, that it is. Trying to pretend our institutions, organizations and careers will always be young and vibrant is hopeless. Wouldn't it be better to embrace change instead and let whatever’s time is over die with dignity?

(forwarded to me)

It's common for people to assume that growth is something essential to every career and organization. I wonder if that's really the case. It's easy to make simplistic statements like “You're either growing or dying”, but isn’t that logical nonsense, based on seeing inanimate objects like organizations as animals? Even animals reach a state of maturity when they no longer grow. And is death always worse than the alternative?

When you think about it more clearly, why shouldn’t organizations die? They have a time when they grow, flourish and fit their environments; then that time is over and they should make way for something else. Prolonging them as they are today by huge infusions of cash isn’t going to change that.

Careers too. Many people find that something is exciting and new for a time, then successful and enjoyable (but essentially stable) for a period, then begins to show signs of aging and incipient failure. Isn’t it best to recognize this, let it go and move on to something different? Why should clinging to a job you now dislike be praiseworthy?

If we want to be realistic about our world (and few people do, much preferring comforting fantasies), we ought to admit that everything—organizations, careers, products, ideas—has a natural life span: some long and some very short. Understanding this natural duration, and where we are within it, is the essential basis for sensible choices.

During the growth period, you may need to make exceptional investments of time or resources to aid that growth. Once established, you need to focus instead on keeping going during a period of maturity. And when it’s time to let go and allow things to pass away to make room for the new, you need to change your actions accordingly.

What I see all the time are futile attempts either to prolong the growth period indefinitely or prevent even the most merciful death. The period of maturity—the period when you should expect to enjoy the benefits from all the effort made during growth—is ignored. Maybe people think it’s too dull.